“The people in flight from the terror behind had strange things happen to them: some bitterly cruel and some so beautiful that their faith is refired forever.” – John Steinbeck, Grapes of Wrath

Leo Hart refired faith.

Maybe Leo Hart, Superintendent of Kern County Schools in the 1930’s, developed his own faith growing up in rural God-fearing Iowa with a school teacher mother and hard-working father. Maybe his convictions grew as he fought in France during World War I, then battled tuberculosis in a sanitarium. With his new-found health, he earned a master’s degree in education, taught in Bakerfield’s high school, then became superintendent of schools. Right in the district where John Steinbeck lived, worked and wrote his novel about the Oakie immigrants. People who left the Oklahoma Dust Bowl with all their earthly possessions in rattle-trap cars to work as migrant laborers for starvation wages in California. Leo Hart’s faith led him to reach out to the disheveled children living in the tents of Weedpatch Camp with belief in the potential of these ragtag waifs.

Classes were held in an airplane. Photo from Arvin Federal Emergency School

Taxpayers and Teachers

Contrast Hart’s faith in these Oakie refugees with the cynicism of the taxpayers in Kern County. The community regarded the newcomers as “uneducable” and their baggy overalls and tattered dresses as offensive to civilized standards. The teachers moved the migrant worker’s kids to the back of the room because their unwashed bodies smelled. The biscuits they brought for lunch caused gagging noises from the local students. Unkempt hair, incomplete knowledge of the alphabet, and lack of school supplies led to both staff and classmates ignoring the Oakies. The humiliated ragamuffins fought back, their spicy language and tight fists flying to their defense.

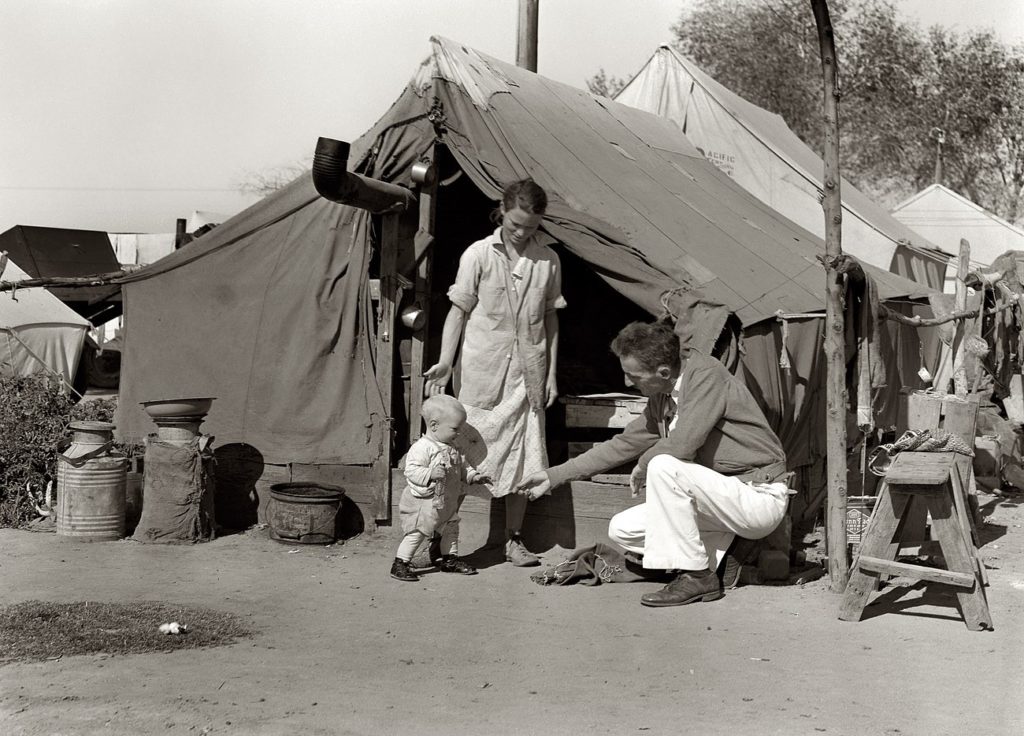

Families from Oklahoma’s Dust Bowl traveled to California with the hope of jobs. WPA photo

The Call of Faith

Hart analyzed the problem. “I needed to find out what to do for these children to get them adjusted into society and take their rightful places.” Watching the dust bowl survivors on the playground, in classrooms and in their camp, Hart realized the effect of years of deprivation on these children’s lives. But he also viewed them as “ordinary boys and girls with the same hopes and dreams as the rest of us have.” With deep faith in the ability of pupils to respond to caring, consistent teaching, Hart began an experiment in building a new kind of school: The Arvin Federal Emergency School. A place for the displaced Dust Bowl kids that would not be associated with the school district. No funding needing. The taxpayers applauded. On the site next to the migrant workers’ camp, Hart started the school with no grass, no sidewalks, no playground equipment, no toilets, no water, no books, no teachers. Just two condemned buildings and “50 poorly clad, undernourished and skeptical youngsters.” And Leo Hart.

Students building swimming pool ~ Photo from Arvin Federal Emergency School

The School of Hard Times

The rest is history. Hart set out to provide the unwanted children “with educational experiences in a broader and richer curriculum than were present in most schools.” During the summer of 1940, he interviewed teachers who wanted an adventure. Then he became a panhandler: a beggar of wood, scrounger of nails, borrower of books and paper. From the National Youth Authority, he received 25,000 bricks, from Sears Roebuck, an assortment of sheep, pigs and cows, from local nurseries, plants and vegetables, from ranchers, farm machinery. In September, Hart met with the faculty and students on a barren stretch of land piled high with bricks, boards, crates and boxes. They all went to work, and brick by brick built the school. The students laid pipe for water. The teachers taught how to make desks from orange crates. In the traditions of George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington, the adults helped the children learn life-giving skills. To extend the curriculum further, a local butcher demonstrated meat cutting, and volunteer cooks helped the home economics class to use the produce that they grew in the gardens. An old boxcar was moved to the school and the boys learned to plaster, add plumbing and wiring. The school became self-sufficient with livestock and gardens, increasing the nutritional intake of the students. An incentive to attain high grades was the promise to drive the airplane up and down the runway. Soon, truancy and behavior problems disappeared. Hart claimed, “We left everything lying around and no one ever stole a thing.”

Migrant workers lived in tents in Weedpatch Camp, California. California archive photo

A Living Legacy

Leo Hart’s personal convictions led him to see potential where others only viewed problems. The children of the Grapes of Wrath who attended a school that they made with their own hands grew up to create businesses, graduate from college, serve on boards, and live useful lives. “It had a happy ending”, Hart says of the four years that the school operated outside the district. Its success opened the arms of the community to the power of education. Faith was refired.

As an undergraduate at University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, I was able to participate in a program that certified its graduates for teaching underprivileged children. The experience changed my life. Reading Leo Hart’s story reminds me of the principles that were taught to all of us rural college interns who knew their cows, but didn’t know about gangs. Like Hart, we wanted to see the potential in every child being realized. It became our passion in life.

Photo by Arthur Rothenstein

Woody Guthrie was an Okie. He sang the songs that the migrant workers from the Dust Bowl recognized. Guthrie’s experience as an emigrant to California mirrored those of the Weedpatch Camp: loss of dignity, deprivation and hopelessness. In his songs, Guthrie expressed these emotions. “They say I’m a dust bowl refugee, and I ainta gonna be treated this way.” Those words from the song, “Goin’ Down This Old Dusty Road” spoke to the Okies who had lost everything in the Dust Bowl and gained hardships in California.

In the novel, Dust Between the Stitches, the residents of Hooverville long to travel to California to get a job and have a better life.

Jerry Stanley’s book, Children of the Dust Bowl, describes the work of Leo Hart from interviews and research that Stanley conducted.

Meme photo: Leo Hart and student, Arvin Federal National School archives

.jpg)

This was a good story about Leo hart.