Cleo Thoughts, Quilts

Piecing a Nation Together: Hilton Head Nine Patch

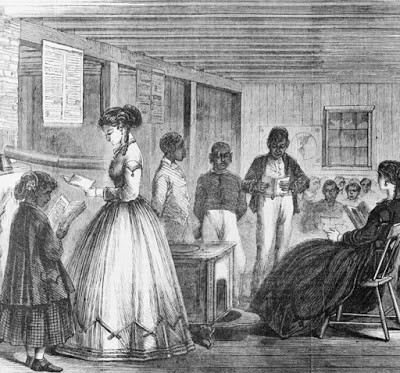

Freedmen’s School on Roanoke Island, Virginia

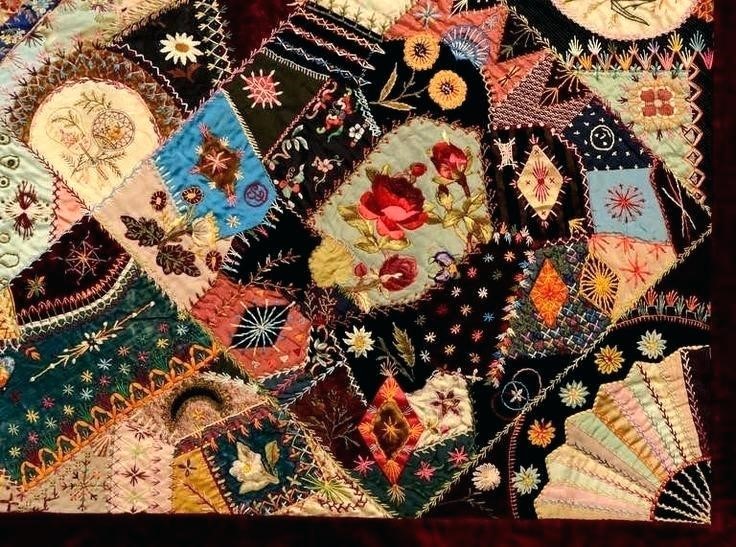

The Civil War ended and the Reconstruction of the nation began in 1865. Lincoln hoped to bind the people back together as one, but soon found how challenging a task lay before him. Frayed pieces of blue and gray scraps, some with red stains that refused to wash out, presented only the possibility of a crazy quilt design. Lincoln longed for crisp edges and exact stitching at the seams, but the material for Reconstruction was irregular, needing creative embellishments and threading. Two organizations provided the ability to begin mending the fragments of a tattered society into a cohesive whole.

The Freedmen’s Bureau was organized to provide relief and assistance to the former slaves including health services, education and agricultural support. The American Missionary Society, a Protestant-based abolitionist group, promoted education for newly freed slaves by establishing schools and colleges, as well as supporting the teachers. The AMA recruited northern teachers for the schools and arranged to find housing for them in the South. The Freedmen’s Aid Society concentrated on teaching farming skills. Embroidering the threads of love in creative stitches, the AMA and Freedmen’s Bureau began basting the scraps of a nation into discernible designs.

Photo by Heardhome.com “Crazy Quilts”

Eliza Ann Summers, AMA Teacher

Eliza Ann Summers sharpened her teacher skills when she began teaching in her hometown of Woodbury, Connecticut in 1863. Like many men and women in the North, she volunteered to teach emancipated slaves. She was assigned to South Carolina with her childhood friend, Julia Benedict. On January 12, 1867, they arrived at Hilton Head Island. Quartered in a small wooden house built for former slaves, the teachers faced Spartan conditions. Two pine shelves, one chair, a box, one trunk, and a bed furnished their bedroom. After Eliza unpacked her few belongings she wrote to her sister:

“I want to tell you about the bed quilt of mother’s. Tell her I think of home every time I look at it and I think how Aunt Ruth and we all worked to quilt it. It is the greatest ornament in the room.”1

Eliza knew that sleeping under a handmade quilt was like being wrapped in a family’s love. Facing difficult times as an educator on an island abandoned by its owners, Eliza needed strength from home.

Five hundred families occupied the hamlet where these AMA teachers were assigned. The three churches housed the educational programs. The two friends conducted day and evening schools for seventy-six pupils of all ages, child through adult, in the “Praise House”. They maintained a Sunday School program, and sometimes led singing. Julia usually shared a sermon from Mr. Brace’s Sermons to Newsboys. Eliza read Scripture at most services because the populace did not have the reading level yet. The teachers conducted funeral services in conjunction with the Black pastors. They joined the islanders for song fests, knotting their souls together with music. For all of these leaders on Hilton Head Island, the moral training and education of the freed men and their families needled a route for binding the islanders to the crazy quilt of the mainland.

2.bp.blogspot.com

Lack of supplies plagued the island and presented challenges to the teachers who creatively taught their students. Eliza wrote home. “We haven’t had any sewing school yet for we have had nothing to sew.”2 It was a part of Eliza’s curriculum to teach the children the art of creating quilts from scraps. But she lacked any material to work with. With anxiety, Eliza awaited a box from home. In addition to sewing supplies, she had requested clothing for the children who arrived barefoot and in well used garments. Tools for teaching and compassion for the needs of her students.

In May, 1867, the box with hand-me-down clothing for the children and several bolts of calico fabric arrived. The time for creating a quilt with Emily’s students brought her joy. Emily writes to her sister:

“I have finished my evening school and feel rather tired as I have had my first sewing school today and taking it all around it has kept me busy. Have not done much else but cut that calico since the box came, and have it cut nearly up.”3

One wonders if Emily did not have enough scissors so that the children could learn to measure and cut fabric. It appears to be the case.

“The children are piecing a bed quilt for me of it. I know that a block or piece or two would not do them and good, and they are perfectly delighted at the idea of doing it for me.”4

The process of learning how to stitch on a seam is Emily’s goal.

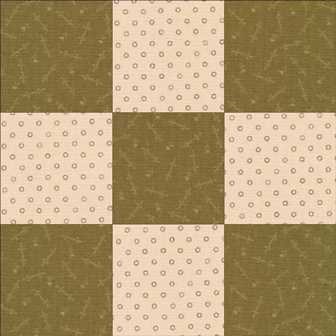

“They have pieced five whole blocks and parts of several others this afternoon. The blocks are just a plain nine square, five dark and four light. “5

So, the stitching, binding and top tying introduced the Hilton Head students with the concept of making beauty from small scraps of fabric. As Emily and Julia labored with the children and adults on this forsaken island, the gentle work of mending hearts, minds and souls drew them all together as one. The teachers taught academics. The islanders shared the knowledge of oyster preparation and how to survive in lean times. Together, the patches of their lives created a coherent whole.

Emily and Julia only taught one year on Hilton Head. Emily returned to Connecticut to marry. She bore four children who cuddled under the comforter that she brought from a place of great deprivation in an era of fragmented dreams. A quilt stitched with fingers eager to learn.

Nine patch

Photo from Homestead: National Monument of America, Nebraska

“Our Constitution was made for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”- John Adams

“Dear Sister”: Letters Written on Hilton Head Island 1867

Edited by Josephine W. Martin, published by Beaufort Book Co; Inc., Beaufort, South Carolina, copyright 1977 by Curtiss and Dorothy Hitchcock.

- Page 14

- Page 70

- Page 83

- Page 83

- Page 83