Cleo Thoughts

Welcome Home, Vietnam Vet

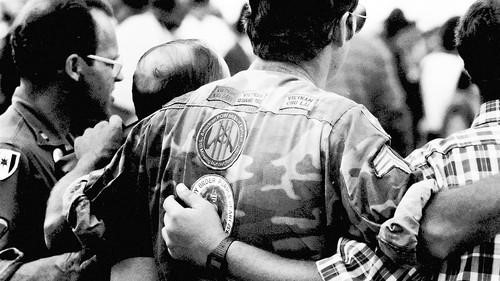

An enthusiastic and emotional “welcome home” honors those who served in the Vietnam War. (Tribune photo by Phil Greer)

On June 13, 1986, I squeezed my way to the curb on Michigan Avenue in Chicago with my three children and two of their friends in tow. The half million people lining the streets of the Windy City’s downtown pressed on our bodies and breathed down our necks. We stood our ground as the police tried to keep us on the curb while shredded paper floated from the high buildings surrounding us. Banners proclaiming “Honor the Warrior, not the War” intermingled with solemn faced women holding framed photos of young men in military dress. Few bystanders in that crowd brushed away the tears that flowed freely down their cheeks. We watched as 200,000 vets clad in camouflage uniforms paraded for five hours on foot, in wheelchairs, or in the arms of comrades. Buses from Hines Hospital rolled slowly so the men inside could wave. Some vets rode in bamboo cages as reminders of the treatment endured by many prisoners of war. Most just marched through the tickertape strewn streets. My children cheered as these men finally “came home.”

Even to this day, the expressions on the faces of those soldiers in mottled green fatigues are vivid. Long hair framing their faces, the sign of rebellion in that era, only focused attention to their eyes. The men who avoided eye contact with the crowd as they surveyed us with suspicion. The slumped soldiers whose hollow gaze told of a broken spirit. Some units of bright eyed comrades who sported short military haircuts and strutted with a cocky gait. We waved and smiled at many who returned the love. Row after row, line upon line they filed by. A sea of faces. Yet a snapshot of individuals. My heart ached as their march blurred off and on all day in my watery watch.

The Vietnam War had impacted my life profoundly. As a high school and college student, the war dominated every conversation. I wrote to several soldiers during this time, not understanding the anger lying beneath their words. Those who did not return left raw emotions and empty holes in the hearts of those who knew them. The War defined so much of my young adulthood. When the city announced that a parade would be held, I told my ten year old son and my junior high daughters that we needed to honor these men. For a farm girl who had never taken the commuter train downtown by herself, much less with children, this was a solid commitment.

Maybe it was the words Tom Stack, chairman of the Chicago Vietnam Veterans Parade Committee, which motivated me to bring history to my children. “During the Vietnam War, you didn’t come home with your buddies,” Tom Stack said. “You got off the plane, trashed your uniform, and went home through the back alley. They are coming to this parade to reunite with the rest of America.” I was struck by the realization that no matter the outcome of the war, the men and women who had fought in Vietnam had sacrificed for their country. They needed a parade of healing.

Veteran Steve Benson brought his son, Mike, to the march and to the copy of the Vietnam Memorial wall in Grant Park. “I wanted to show my son the closeness and friendships between the veterans, and I wanted him to meet guys that I fought with and know what we went through. I think after today, I’ll be able to talk about it a little more openly with him than in the past. I feel like I have had a ton of bricks taken off me. I’ve cried, and I wasn’t alone.”

Veteran Steve Benson brought his son, Mike, to the march and to the copy of the Vietnam Memorial wall in Grant Park. “I wanted to show my son the closeness and friendships between the veterans, and I wanted him to meet guys that I fought with and know what we went through. I think after today, I’ll be able to talk about it a little more openly with him than in the past. I feel like I have had a ton of bricks taken off me. I’ve cried, and I wasn’t alone.”

On this Veteran’s Day, I remember my classmates who served. I remember a childhood friend who died on foreign soil. I remember the cost of my freedom. And I remember to be grateful to those who have paid the price.

“Never again will one generation of veterans abandon another!”

-Motto of Vietnam Veterans of America

PTSD haunts the lives of America’s veterans. Joe Malinkovich is a medic who suffers from PTSD, but receives help at the VA. Veronica Bagadonas falls in love with Joe as he contributes to her special education classroom. What lies in the future for a couple with challenges? Read Miss Bee and the Do Bees, by Cleo Lampos from the Teachers of Diamond Project School Series.