Cleo Thoughts

Irish Immigration and the Orphan Trains Changed the Direction of my Life

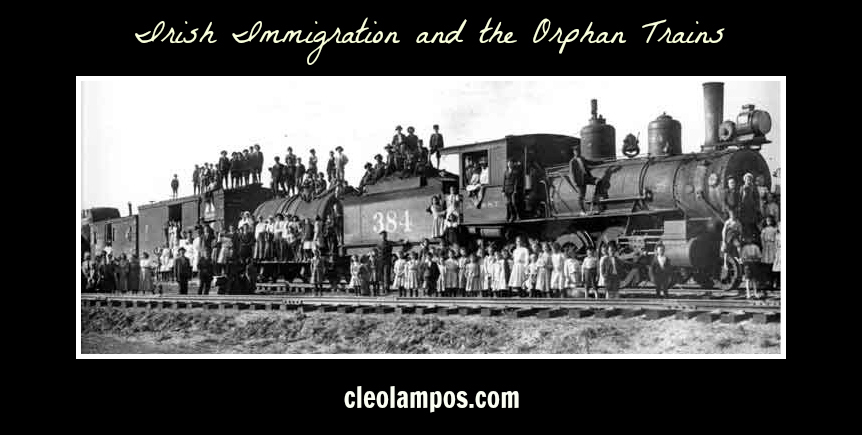

The gift shop shelves heaved with books covered by grainy photos of children huddled around coal driven steam engines. Dressed in turn of the century clothes, some ragamuffins carried grief like luggage, but others appeared wide-eyed with adventure. “Orphan trains,” my brother explained. “Those children were adopted here in the St. Cloud, Minnesota area. They spoke in the school system for years about their experiences.” I bought an armload of books.

The gift shop shelves heaved with books covered by grainy photos of children huddled around coal driven steam engines. Dressed in turn of the century clothes, some ragamuffins carried grief like luggage, but others appeared wide-eyed with adventure. “Orphan trains,” my brother explained. “Those children were adopted here in the St. Cloud, Minnesota area. They spoke in the school system for years about their experiences.” I bought an armload of books.

Endless Homeless Children

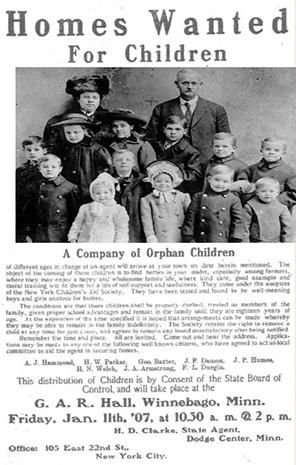

Subsequent research detailed how an average of 300 homeless urchins every month for 70 years rode the orphan trains. Did anyone miss even one of these children? They escaped from Five Points, New York City to be adopted by church sponsored families on farms in the Midwest. The flow stopped in 1930. But what kind of mother put children on these trains, and how well did the children do in their new homes?

The Birth of Foster Care

For two years, I read every book, magazine article, or Google account. My husband and I attended the Little Falls Orphan Train Reunion and met four elderly riders. We traveled to Concordia, Kansas, and researched at the Orphan Train Museum. Then, I realized how the suffering of Irish immigrant women contributed to the homeless waifs overflowing onto the streets of New York City. Women who could no longer care for their children gave them up to the chance of a new life through what we now call foster or adoptive agencies.

Reading the accounts of these riders as they tried to assimilate into the Midwest proved to be inspiring and heart wrenching. Most eventually made the transition. Some never did. The adoptive families faced overwhelming challenges. But, agents of the Children’s Aid Society, like Clara Comstock, rode the train with the children, settled them into their homes, and checked on them every year. These agents introduced the class of social workers of today with their grit and determination to meet the needs of traumatized children.

Ava Rose rides the orphan train as preschooler, but becomes a courageous Nebraska teacher.

Spreading the Story

Of course, a book, A Mother’s Song, resulted from this research. The overflow of knowledge produced published magazine articles and chances to speak to senior classes, book clubs, and genealogy groups. I have met so many interesting people because of these opportunities to write and speak as a retired educator.

In A Mother’s Song, Deirdre O’Sullivan gives her children to the orphan train so they will survive, but she spends the rest of her life fighting for the rights of women so they will not have to make the difficult choices that she once made.

An awareness of how Irish immigration led to the greatest movement of children in the United States has been the result of my search into history. And it all started in the gift shop of a museum.

“The work was a great adventure in Faith: we were always helped and grew to expect kindness, deep interest and assistance everywhere. We were constantly attempting the impossible…I thought it the most incredible thing imaginable to expect people to take children they had never seen and give them a home, but we placed them and never failed to accomplish it.”- Clara Comstock’s speech in 1931 to Children’s Aid Society Staff

“The work was a great adventure in Faith: we were always helped and grew to expect kindness, deep interest and assistance everywhere. We were constantly attempting the impossible…I thought it the most incredible thing imaginable to expect people to take children they had never seen and give them a home, but we placed them and never failed to accomplish it.”- Clara Comstock’s speech in 1931 to Children’s Aid Society Staff

Cleo Lampos is a retired teacher of behavior disordered students. A foster child herself, Lampos understands the difficulties of broken childhoods. An author, teacher and storyteller, Lampos wrote A Mother’s Song, a novel about two mothers and the child who loves both of them.