Cleo Thoughts, Quilts

Remembering Hobos With a Code Quilt

“I know every engineer on every train,

All of their children and all of their names,

And every handout in every town…..”

-Ralph Miller, King of the Road

Maralyn Dettmann

No one wanted to be a hobo. But choices lessened as the Great Depression of the 1930’s deepened into a decade of drought and despair. With an unemployment rate of 25%, chances for a job dwindled. Teens left home so there would be one less mouth to feed. At the height of the Depression, more than two million men, 8,000 women, and 200,000 children rode the rails around the country trying to survive. Trying to find work. Hobos were men who agreed with Eleanor Roosevelt who observed: “Only a man’s character is the real criterion of his worth.”

Hobos sought employment. Tramps worked when forced by the police. Bums never worked. It was hobos who traveled like migratory birds atop trains as they followed the agriculture’s seasonal needs. Many traded their skills in shoe repair, gardening, crafts or music for food on a back porch. One thinks of Burl Ives and Woody Guthrie “singing for their supper”, or entertaining fellow travelers over a tin can of Mulligan Stew. Pete Seeger speaks for these hungry musicians: “I have sung in hobo jungles, and I have sung for the Rockefellers, and I am proud that I have never refused to sing for anybody.”

Although hobos lived hand-to-mouth existences, their goal was to send money back home to parents or a wife with children quartering with relatives.

The central gathering place for hobos was the jungle, or camp. The location site partnered with a water supply and the nearness of the railroad, but out of range of the city folk. Birney Dibble remembers the hobos in his area of Eau Claire, Wisconsin. “I learned that the hobos had a written ethical code. Decide your own life. Respect local laws. Try to find work. Don’t be a drunk. Clean up your garbage. Induce runaway children to go home.”

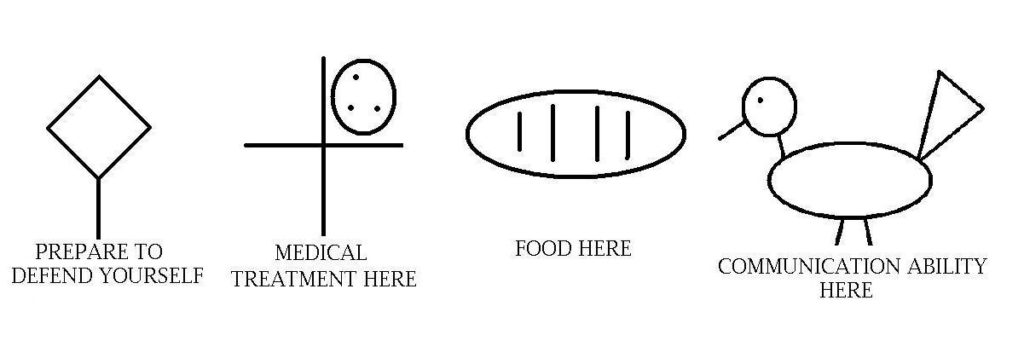

From National Archives

The ‘bos helped each other to navigate a city. Using a secret code, they warned each other of danger and guided hungry souls to soft hearted housewives. The code was carved on fence posts, stair steps, over doors, on the bark of trees. Using simple straight lines and curves friendly to a pocket knife, one ‘bo prevented the aggressive police or citizens from harming fellow travelers. Code signs warned of mean dogs, unhealthy water or chain gangs.

The Hobo Code provided the ‘bo with courage to knock on a door to ask for work in exchange for a bite to eat. A side view drawing of a kitty cat near a door indicated a kind woman. Patricia Schreiner recalls: “The women all said that if one of those hobos was their son or husband, they would like to think that some housewife was giving him a bowl of soup or a sandwich.”1

Maybe some church goers were familiar with the Scripture that admonishes: “Be not forgetful to entertain strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.” Hebrews 13:2 KJV. Many of the men who lived as hobos eventually found their life work: Jack London, Louis L’Amour, and Jack Dempsy. Art Linkletter speaks for these men: “I grew up poor. I never had any money. I was a hobo, you know, ride the freights.”

In the code, a stylized T indicated that a ‘bo could work for food. A simple cross indicated that the hobo should talk religion to get a bite. The sign of a shovel promised that work might be available. Reading the code helped the men with colorful names like Box Car Willie, North Bend Fred, Shorty Montana, Slim Pickings, or Detroit Dan to survive the constant dangers of homelessness.

From National Archives- Hobo Markings: Language of Survival

“My experiences made me a lot more humble and I appreciate the smaller things in life- like a good bed and something to eat.”- Archie Frost 2

Putting the Hobo Code on Fabric

To commemorate the pluck and perseverance of these legendary Knights of the Road, Debra G. Henninger wrote a book, Hobo Quilts. She includes many vignettes and remembrances of people who lived in the Great Depression. These accounts warm the soul with their words of compassion for the downtrodden men as well as the sacrificial sharing from limited pantries. Ruby Le Munyan expressed it best. “We didn’t have much, but we knew we had a lot more than the people who stopped by.” 3

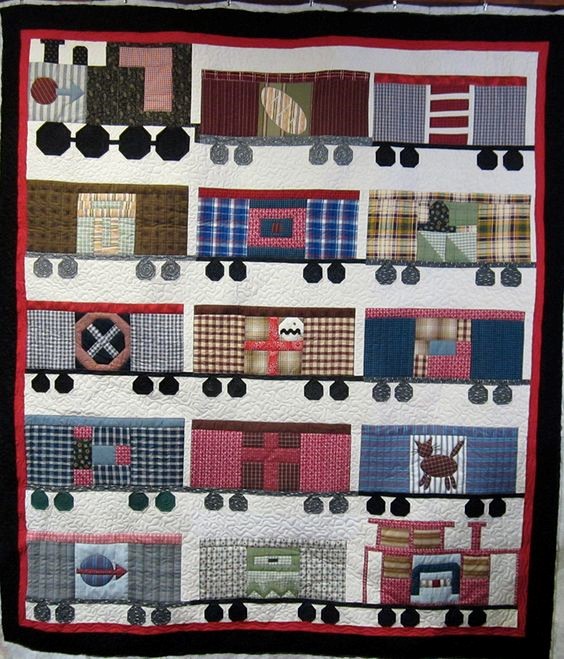

Henninger includes instructions for creating a quilt square for each of the 55 symbols used by the hobos. She uses individual designs to emphasize a message in unique quilts. My favorite is the one with boxcars rolling across the cloth in celebration of the railroad. Another quilt is covered with spades, emphasizing the agonizing desire of ‘bos to work.

Saved by Rosy Mandel

The breathtaking finale is a quilt that incorporates all the symbols of survival utilized by the hobos. This masterpiece of historical information is a reminder that in the darkest of times, the human soul reaches out to one another in compassion. A mortal hand clasping the palm of an angel in frayed disguise.

The most heart wrenching fact about this era lies in the name given to those teens and men who wanted to labor and earn their keep. Hobo. The word is a shortened expression from the depths of these wanderer’s hearts.

Hobo means “homeward bound.”

Hobo Quilt by Debra G. Henniger with over 55 unique block designs from her book, HOBO QUILTS.

References: Hobo Quilts: 55+ Origianal Blocks Based on the Secret Language of Riding the Rails, by Debra G. Henniger

- Page 29

- Page 79

- Page223