Cleo Thoughts, Quilts

Trail Quilts: Comforters on the Covered Wagon

“There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made.”

-Willa Cather

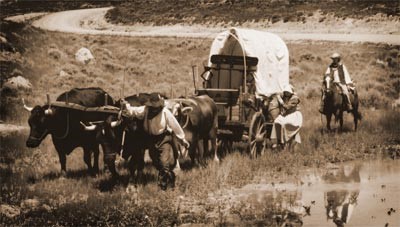

The oxen leaned into the yoke, pushing against the wood with their sinewy strength. Under the weight of the covered wagon, the iron rimmed wheels grated against the gravel cutting ruts of legacy. At the beginning of the Oregon Trail, the wooden wagon could take a load of a ton and a half at the most. A toolbox on one end, water bucket on the other, and a grease bucket in between. Lying on the bottom of the carriage box were the heavier supplies like a plow, spinning wheel, stove, bags of seed and a chest of drawers. On the wooden sides all the kitchen utensils and clothes were strapped securely. The top layer displayed the daily necessities: flour and salt, water keg, cooking pot, the Family Bible, a rifle, an ax, as well as folding campstools.

And a stack of handstitched, neatly tied, scrappy patchwork quilts.

These piles of folded fabric provided a tangible anchor for the women on the long trip from St. Louis, Missouri to Walla Walla, Washington. The women would be tested physically and spiritually on the journey via the Oregon Trail in the early 1800’s. Comforters in the wagons would sustain them.

Quilts as Emotional Therapy

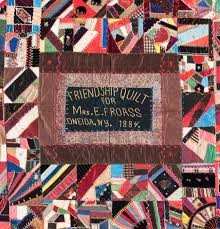

Quilts provided emotional support for the pioneering ladies. Knowing that a move half way across the continent would be permanent, the families staying back East created a connection to the ones on the journey over the mountains. A album quilt was secretly made by friends and relatives, each contributing a square or two. This “good-bye hug in cloth” contained signatures, quotes and messages needled in embroidery and applique. During the loneliness of the prairie, the solitude of the desert, the danger of the mountains, and the darkness of the nights, the prayers and concern of loved ones back home warmed the souls of those who lived each day by faith. The pangs of homesickness lessened as a finger traced a Bible verse stitched with thick embroidery thread.

As a woman unpacked the quilts each night for the family to sleep upon, the designs on the fabrics brought her heart back to what home means. Growing up, the remnants created from the making of clothing were placed in a scrap bag from which patchwork quilts grew row by row. Each square represented a shirt, a dress, a vest, or a coat that had been worn by a member of the family. These fabric memories helped keep the extended family near. As the quilts were folded in the morning, or aired out on rocks, loved ones lingered just a thought away. Putting the needle and thread to the holes and rips in the material of her quilt, the pioneer woman patched her quilts as she bound up the frayed and ragged edges of her mind and emotions.

The intricately designed quilts created with applique or tiny embroidery stitches were utilized to caress the dishes and other delicate items that would be unpacked in the new land. Their specialness would be appreciated in a new home with no way to create quilts until the flax was grown and harvested, and new fabric made. The women carrying their babies as they walked alongside the oxen drew emotional support knowing their artistic comforters were safely packed inside the wagon’s box.

Barbara Brackman’s Material Culture- Blogger July 30, 2017

Quilts as Physical Protection

The everyday quilts provided protection for the family. They were targets for arrows as they hung from the exposed side of the wagons during Indian attacks. These utilitarian comforters afforded padding on the wagon seat, shelter from the winds, or as a cover over the cracks and openings that let in the choking dust or icy air. At night, their layers snuggled the children and adults from both the bottom and the top, especially if they were sleeping outdoors.

National Oregon/California Trail Center, Montpelier, Idaho

Quilts as Burial Shrouds

Quilts helped the pioneers face death. “There were twenty thousand deaths on the Oregon Trail: one out of every seventeen pioneers was lost en route. It is estimated that there was an average of one grave every eighty yards between the Missouri River and the Williamette Valley, Oregon.”1 Cholera, diphtheria, cattle stampedes, water crossings, accidents, and exhaustion claimed the lives of many. In making coffins, a board from each wagon was donated to create a container just the size of the deceased. Wrapping a person in a quilt was a means of giving one last caress and a way to keep the family link intact. A final act of love in a brutal world. Quilts served as burial shrouds that enfolded the fallen as a grieving community gathered to be sure Scripture was read, “broken Hallelujahs” sung, and gravel gently placed over the gravesite.

As Willa Cathers observed, “People live through such pain only once. Pain comes again- but it finds a tougher surface.”

Quilts as Identity

The fabric masterpieces provided a family with a cultural identity. Wagon trains were composed of at least 30 wagons with large numbers of livestock and sheep accompanying the settlers in the four to six month journey. The congregated women admired each other’s quilts and soon traded scraps of fabric from their own stash of remnants. The rawness of life needed to be offset by the creative juices that bubbled within the womenfolk. Sitting by the campfires, new patterns for quilt squares emerged from the accumulated strips of cloth from newly acquired friends.

The Pin Wheel design reflected the power of the wind that blew against the cloth-covered wagon.

Early pinwheel quilt

Early pinwheel quilt

The Wheel design reminded the women of the importance that the wagon wheel was to their journey. Birds, stars and animals fell under the needle and thread to create memories of the things that the women felt and experienced on their way to a new life. Their emerging identity as pioneers.

After chores were done, these sisters on a unique journey lingered by the burning wood. They whispered their fears and doubts while their children slept. With one blended voice they shared hymns and testimonies of their faith as the embers glowed in the star light. Janette Oke summarizes this exchange of personhood. “Having someone who understands is a great blessing for ourselves. Being someone who understands is a great blessing to others.”

Sharing identity.

Sharing cultural.

Sharing self.

Sharing scraps of fabric.

Wheel turn by wheel turn, the trek on the Oregon Trail progressed.

Stitch by stitch new quilt s were sewn to chronical the pain, comradery and triumph of the Trail.

A pioneer woman visualized faith in the midst of life’s journey- one square at a time.

“There’s no place you can go on the prairie that you don’t hear the white noise of the wind, steady and rough as surf curling along a non-existant shore.”

-Diane Ackerman

- 54, “ Hearts and Hands: The Influence of Women and Quilts on American Society,” by Pat Ferrero, Elaine Hedges and Julie Silber.

Photos: Pinterest